Thinking in Structures: Evaluating Spatial Intelligence through Reasoning on Constrained Manifolds

Thinking in Structures: Evaluating Spatial Intelligence through Reasoning on Constrained Manifolds

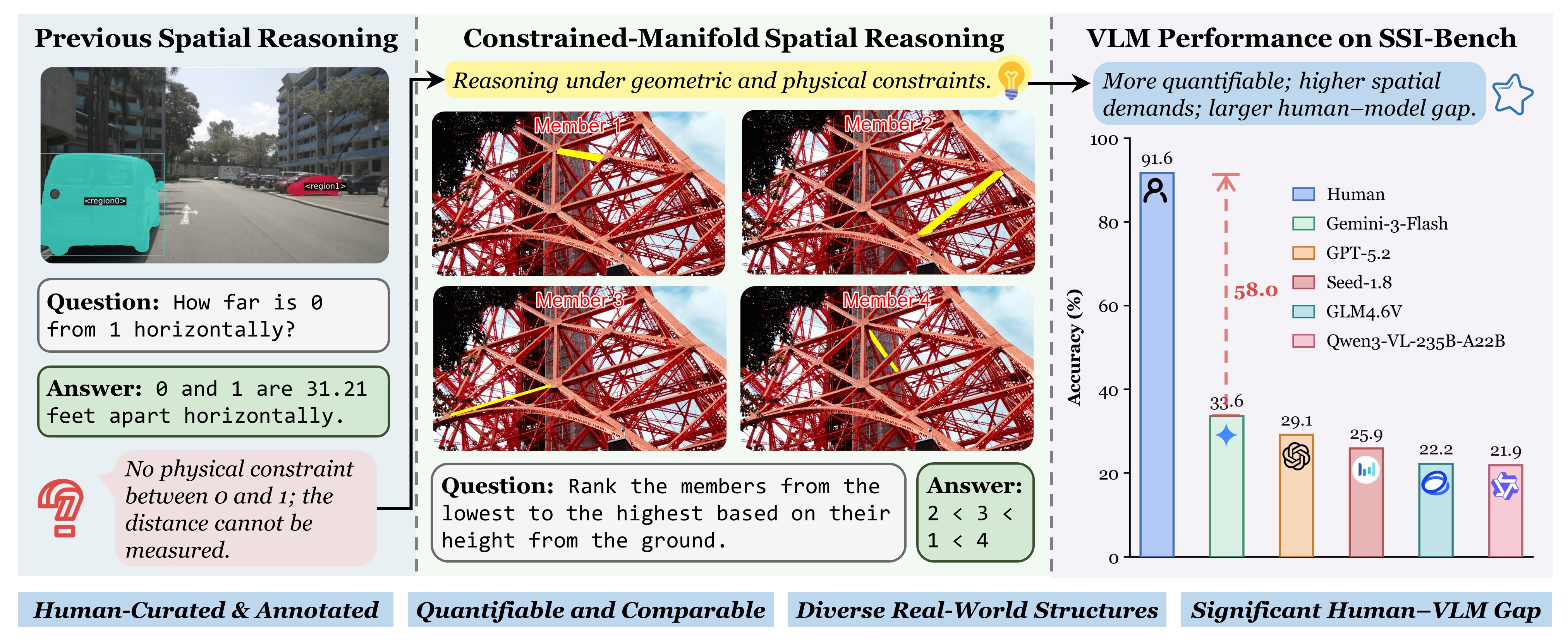

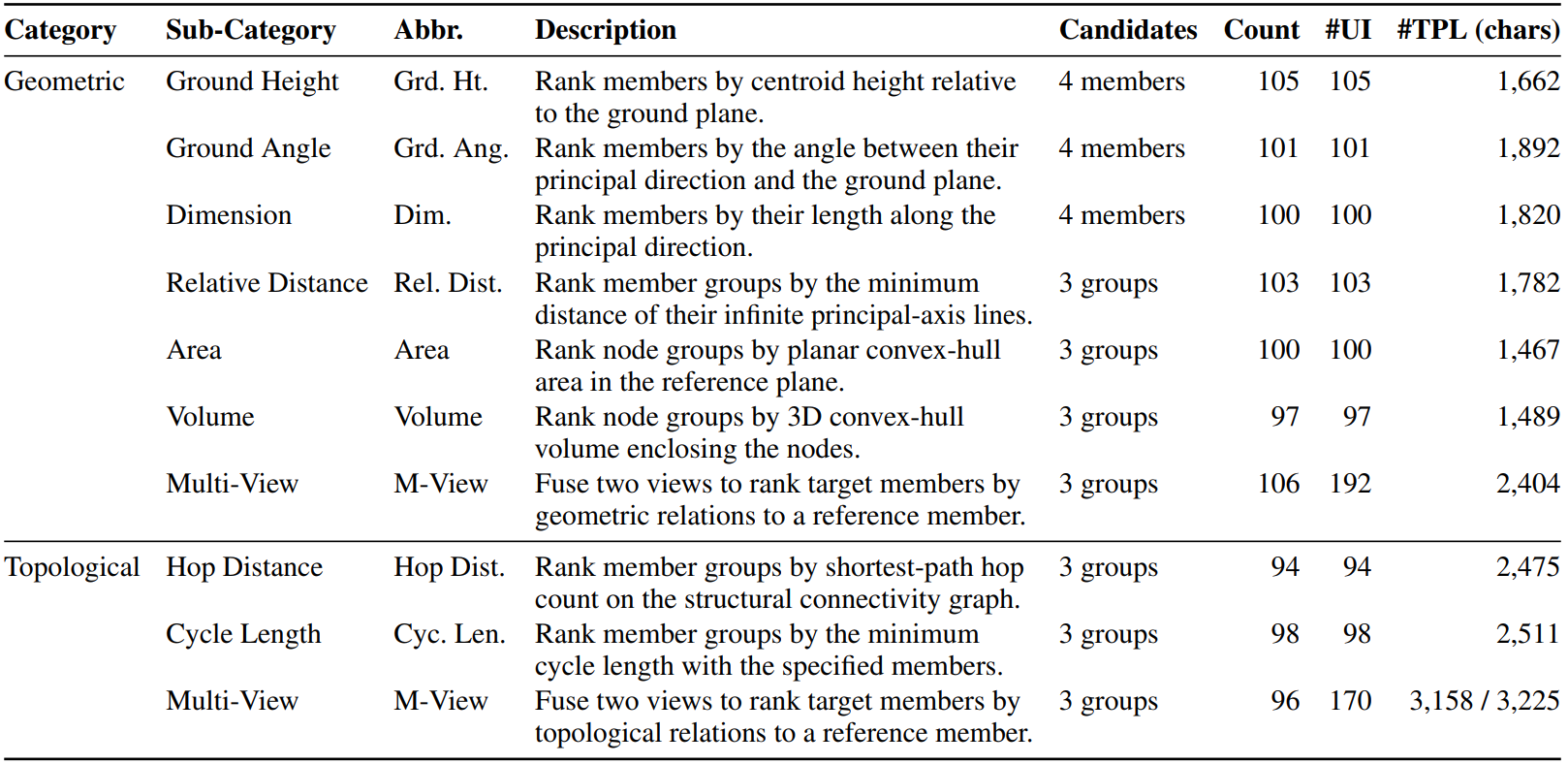

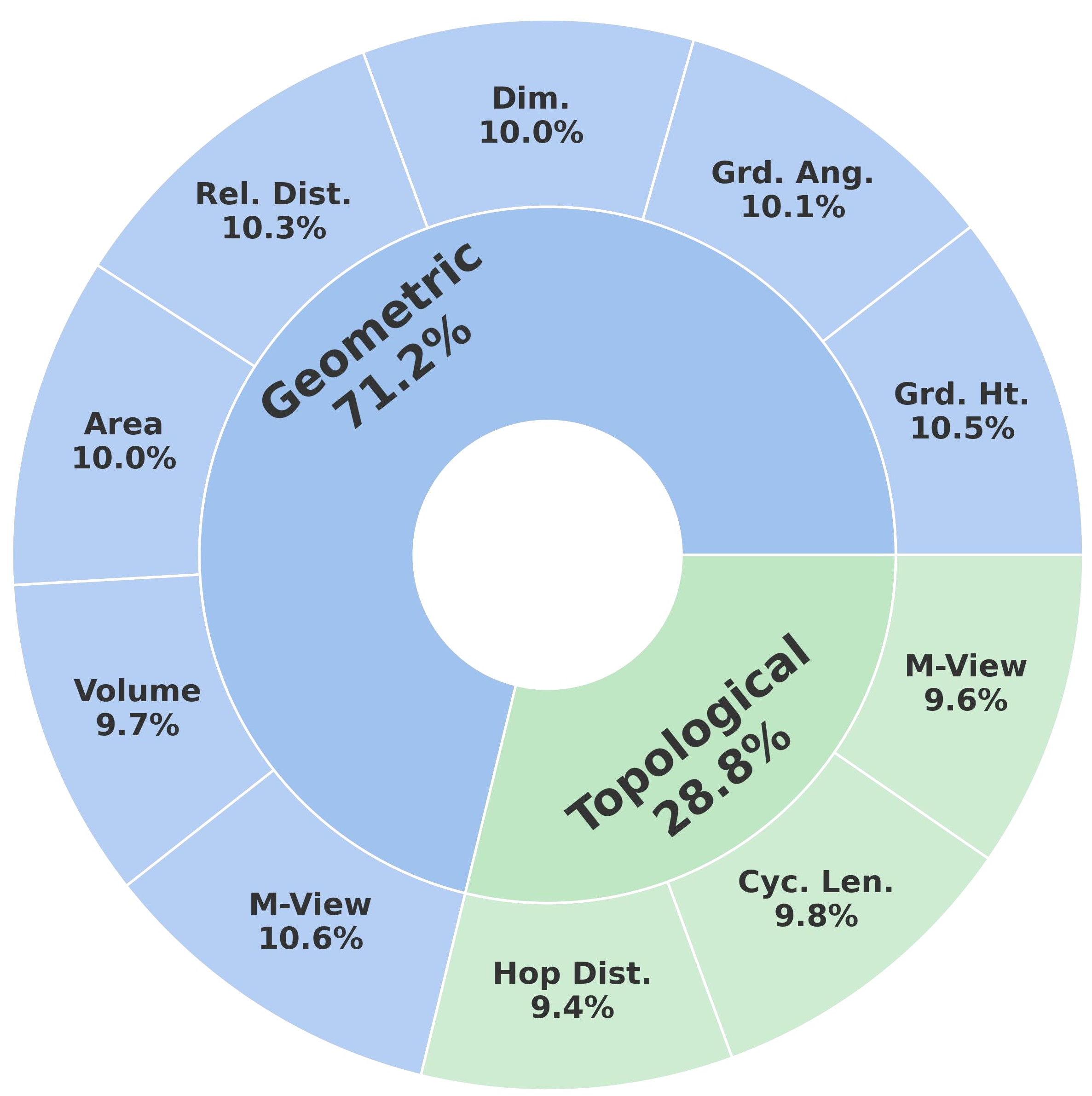

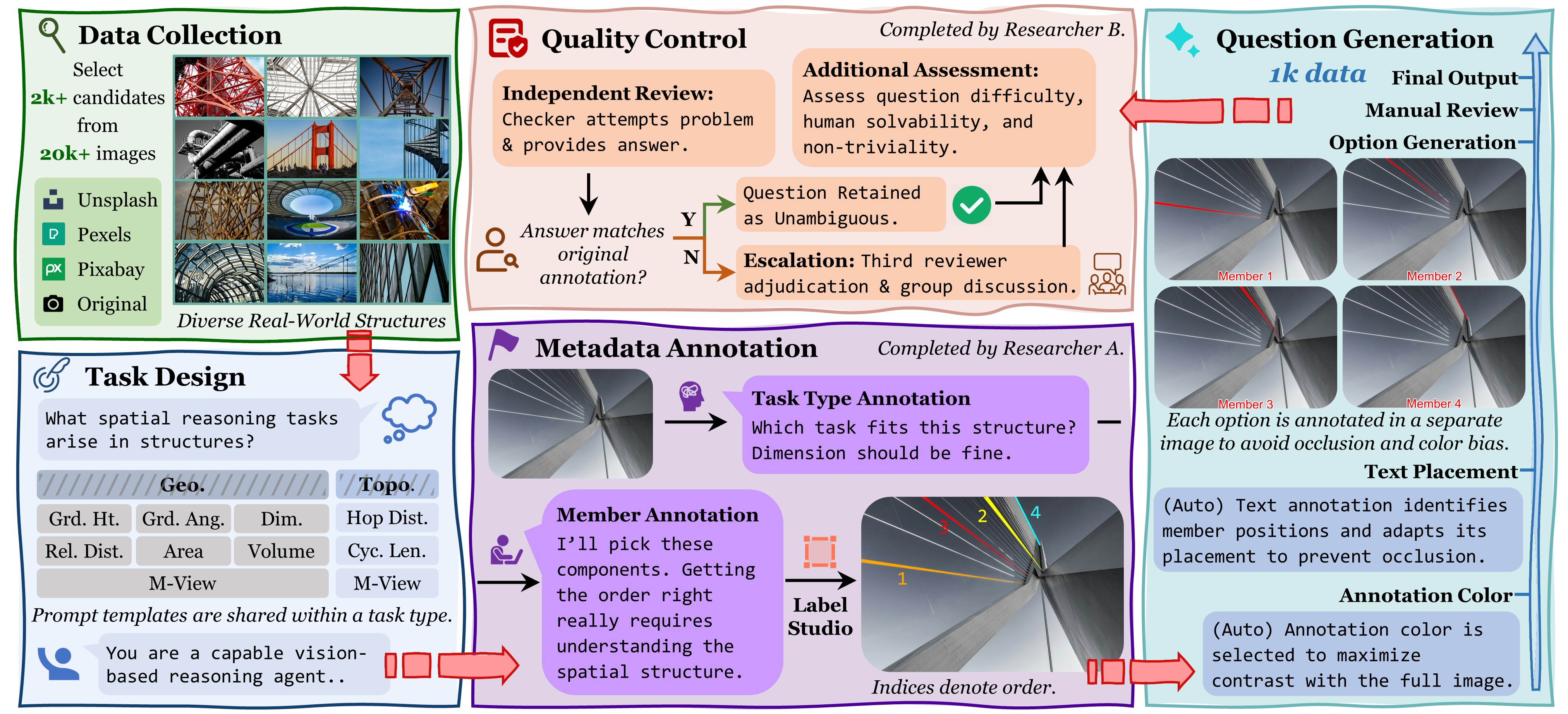

We introduce SSI-Bench, constructed from complex real-world 3D structures with feasible configurations tightly governed by geometric, topological, and physical constraints.

Tsinghua University

Dataset

Explore the CMSR task taxonomy and dataset composition, browse samples in the interactive viewer, and see how SSI-Bench is constructed.

Overview

Dataset Viewer

Construction Pipeline

Leaderboard

Performance comparison of different models on SSI-Bench. Dark highlighting indicates the best result within each category, light highlighting denotes the second-best.

Analysis

Key results, thinking impact, and representative failure modes on CMSR—highlighting where current VLMs succeed, where they fail, and what is still missing for constraint-consistent 3D reasoning.

Key Results

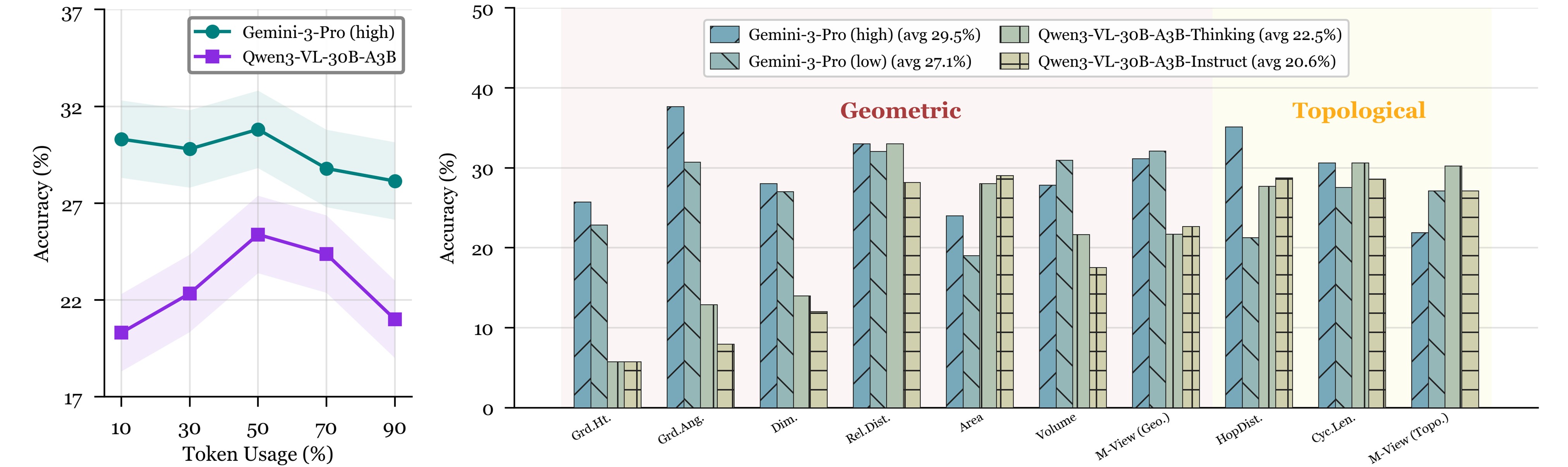

Impact of Thinking on CMSR

- Modest gains: Gemini-3-Pro improves from 27.1% (low) to 29.5% (high); Qwen3-VL-30B-A3B improves from 20.6% (Instruct) to 22.5% (Thinking).

- Token usage is a weak proxy: accuracy is non-monotonic and often peaks at moderate usage, where extra tokens can reflect uncertainty rather than better inference. Very high usage can correspond to longer deliberation over an incorrect structural hypothesis.

- Task-dependent effects: thinking helps more when evidence is stable, but can be mixed or negative on 3D-consistency bottlenecks (e.g., Multi-View and Volume).

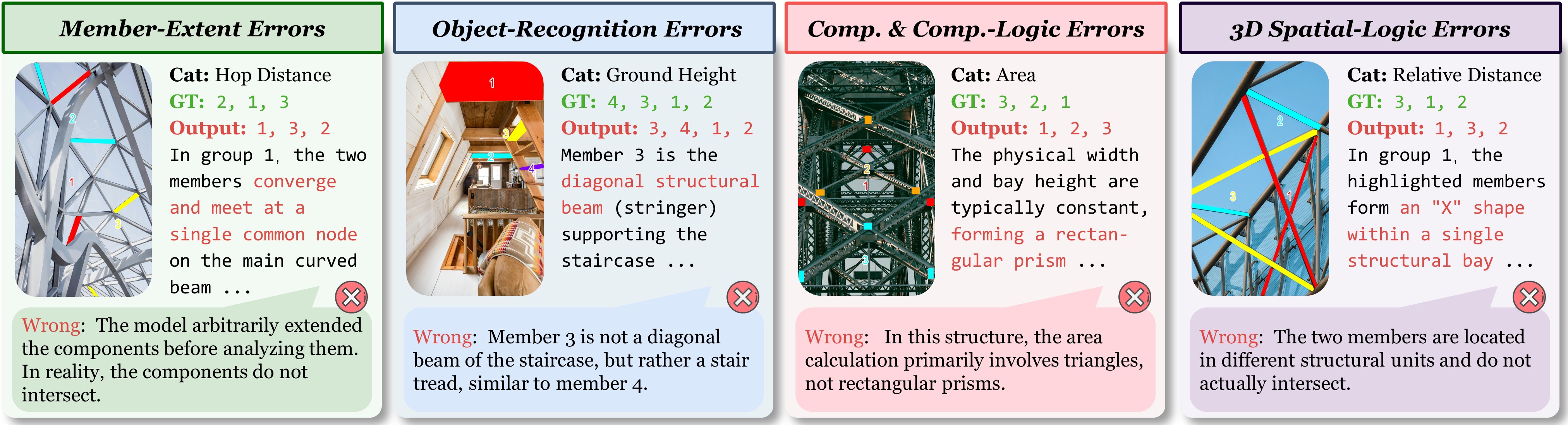

Error Analysis

- Member-extent: over-/under-extending members under occlusion and clutter, breaking endpoint-based comparisons.

- Object recognition: misidentifying components/nodes and coarse orientations, hurting criteria like Ground Angle.

- Computation & logic: optimizing the wrong quantity (e.g., 2D area vs. 3D volume) or applying invalid simplifications.

- 3D spatial logic: weak depth and cross-view correspondence; unstable relational composition in Multi-View settings.